The Menstrual Cycle

You may think that your period affects you only for a few days each month. But your menstrual cycle — controlled by hormonal fluctuations — is full-time. Each month, rising and falling levels prepare your body for a possible pregnancy. As soon as one cycle ends (and you don’t get pregnant), another begins. It’s a 24/7/365 job.

Everyone’s experience with their cycle is different. Some people suffer from debilitating cramps, while others might experience increased acne or mood changes. We’ll explain the biology of how your menstrual cycle affects your body throughout the entire month, not just during your period, and how and when it can help to track your cycle.

The 4 stages of the menstrual cycle

Your period, when your body expels blood and extra tissue from the ,1 is the start of the menstrual cycle. Your period usually only lasts three to five days, but the menstrual cycle, which starts on the first day of your period and ends on the final day before your next period, commonly lasts 21 to 35 days and has four phases.

Stage 1: The menses phase

The menses phase is triggered by a drop in the hormones and , which signal to your body that you didn’t get pregnant this cycle.

Menstruation begins when your starts to shed its , a lining it formed to support a fertilized egg. That extra tissue, egg, and blood exit through your for several days. For most people, the period lasts three to five days, though anywhere from two to seven days is considered normal.

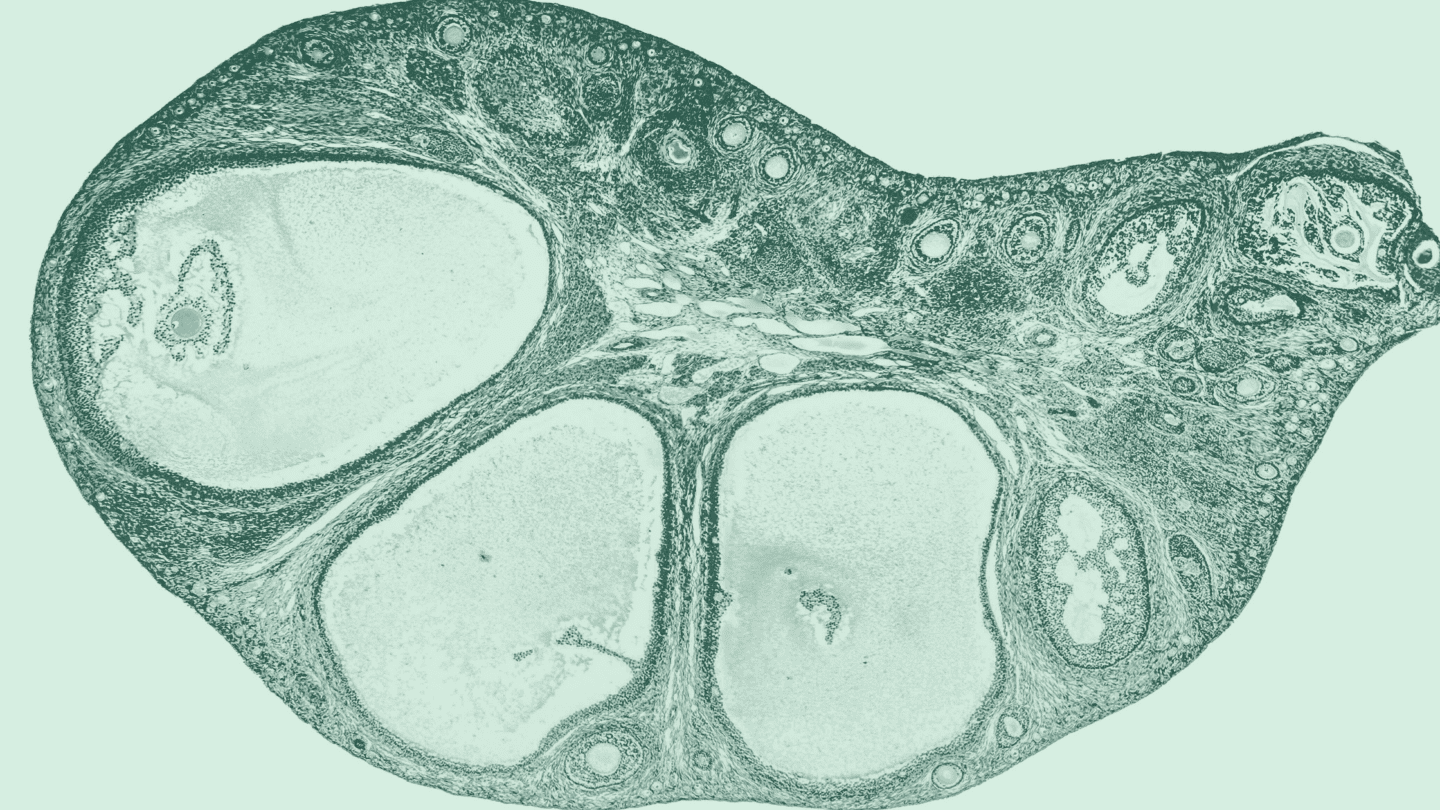

Stage 2: The follicular phase

Once you’ve shed all that extra endometrial tissue, your levels start rising, telling the it’s time to start thickening again. From days 6 to 14, the endometrial tissue thickens and prepares for the delivery of a new egg. Near the end of that process, between days 10 and 14, follicle stimulating tells your it’s time to prepare new eggs for fertilization. A few eggs will mature, but typically3 only one will be released in the next stage.2

Stage 3: Ovulation

Around day 14 of the menstrual cycle, triggers the release of the matured egg from your into your fallopian tubes on the way to your .

Stage 4: The luteal phase

From days 15 to 28, your level rises as the egg travels through your fallopian tubes, eventually reaching your . If your egg meets a sperm in the fallopian tubes, you may become pregnant. Your releases chemicals that either help an early pregnancy attach — if the egg was fertilized — or break down the uterine lining if it wasn’t. In the latter case, you’ll head back to the menses phase, shedding that extra tissue, egg, and blood.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

Menstruation throughout life

Puberty typically starts around age 8 to 13 when your body begins making gonadotropin-releasing (GnRH).3 That in turn stimulates the release of and , key players in the menstrual cycle, which go on to raise levels. The rise in then triggers physical changes and menstruation.

Most people get their first period around the age of 12, though anywhere from 10 to 15 is considered normal.3 If you haven’t gotten your first period by age 15, it may be time to consult a doctor.

In the first few years, your menstrual cycle may be somewhat unpredictable, but after six years, it should settle into a regular 21–35 day rhythm.3 If it doesn’t, you should consult your physician. This regular rhythm will last another three to four decades, until you enter .

The transition to typically occurs between the ages of 45 and 55 and can last from 7 to 14 years. Once you’ve gone 12 months without a period, you are considered to have entered .

In the time leading up to , called perimenopause, your body produces inconsistent amounts of and .4 This can cause irregular periods, as well as some of the classic symptoms of like hot flashes and trouble sleeping. Hormonal replacement therapies, like low-dose , can help ease these symptoms. If you have a — a surgery in which your is removed — you may start sooner.

Menstrual cycle tracking chart (Photo by cottonbro from Pexels)

Period Tracking

There are calendars, cell phone apps, and charts designed to help you track your period. But why would you want to track your period to begin with? A few reasons include:

- So you can be prepared with hygiene products

- So you know when you’re ovulating and likely to get pregnant

- So you know when you’re NOT ovulating and unlikely to get pregnant

- To alert you to irregularities that may signal health problems like 5

Some people use period tracking as a form of , especially if they don’t like the way oral contraceptive pills or other contraceptive methods make them feel. If you track your period very carefully, it’s possible to estimate which days you’re most likely to get pregnant and avoid unprotected sex on those days.

Is adyn right for you? Take the quiz.

The easiest way to track your period is to mark each day during which you have your period on a calendar. The length of your cycle is from the first day of your period to the first day of your next period. You can also write down any changes in mood, pain, or flow to identify patterns.6

But period tracking is not a perfect solution. A 2018 study suggests that because there is significant variability in the length of menstrual cycles, the calendar method (using either a physical calendar or a period tracking app) may not accurately predict the day a person would ovulate.7

Oral contraceptives, s, condoms, and other methods are much more effective at preventing pregnancy.8 Learn more about the types of available and how to make an informed choice.

-

- Reed, Beverly G., and Bruce R. Carr. “The normal menstrual cycle and the control of ovulation.” (2015).

- Intermountain Healthcare. “Ovulation Made Simple: A Four Phase Review.” IntermountainHealthCare.org. (2014 Feb 28).

- Knudtson, Jennifer and Jessica E. McLaughlin. “Puberty in Girls.” Merck Manuals. (2019 Apr).

- National Institute on Aging. “What Is Menopause?” NIA.NIH.gov (2021 Sep 30).

- McKillop, Mollie, Lena Mamykina, and Noémie Elhadad. “Designing in the dark: eliciting self-tracking dimensions for understanding enigmatic disease.” Proceedings of the 2018 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (2018).

- NIH Office of Communications. “Other Menstruation FAQs.” NICHD.NIH.gov (2017 Jan 31).

- Johnson, Sarah, Lorrae Marriott, and Michael Zinaman. “Can apps and calendar methods predict ovulation with accuracy?” Current Medical Research and Opinion 34.9 (2018): 1587-1594.

- Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. “Contraception.” CDC.gov (2022 Jan 13).