It’s likely happened to all of us at some point or another — you’re dealing with a serious medical issue, and bring it to your doctor in hopes of relief. Instead, your symptoms and experiences are downplayed, dismissed, or glossed over.

Medical gaslighting happens when a doctor or medical practitioner denies your symptoms, blames your condition on psychological factors, or doesn’t give your concerns the time and attention they deserve.

Not only is this practice downright wrong, but it also has serious consequences and long-lasting effects on patients. This type of treatment can severely delay or deny a patient’s ability to receive proper treatment for their conditions.1

What’s worse, gaps in quality of medical care are especially prevalent towards women, minorities, and LGBTQIA+ people.2

LGBTQIA+ communities often struggle with disclosing their sexual orientation to clinicians due to fear of lesser-quality care or straining their relationship with providers.

And one study found that women who went to the ER with severe stomach pain had to wait 33% longer than men3 who had the same symptoms.

The danger of insufficient medical care also reaches further for Black, American Indian, and Alaskan Native women, who are 2 to 3 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes4 than white women.

While this statistic is due to a variety of causes, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported these pregnancy-related deaths were preventable, and could be partially addressed through implicit bias in healthcare.5 In other words? Sometimes, medical practitioners aren’t listening to — or believing — their patients’ pain.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

What Looks Like

Most of us are raised to trust the opinions and recommendations of medical professionals, so sometimes it can be hard to identify whether you’re experiencing .

Here’s what that might look like:

Dismissing or sidestepping your symptoms. You may feel that your medical care provider isn’t taking your concerns of pain or symptoms seriously. That includes dismissing those symptoms altogether, or not escalating or carefully exploring possibilities based on your experience.

Saying a certain medication doesn’t have a certain side effect when it demonstrably does. For example, your doctor may tell you that birth control pills don’t cause depression, when you know in your gut they’re the main cause.

Downplaying physical or mental pain. Your medical provider may not believe the level of pain you are actually experiencing, and tell you it’s not a major concern. This happens often to female patients presenting chest pain. One study found that men are 2.5 times more likely to be referred6 to a cardiologist for chest pains than women.

Medical gaslighting puts the burden on you as the patient to advocate for yourself. So, how do you do that when your medical provider doesn’t believe or downplays your symptoms?

How to Advocate for Yourself

Find a doctor you trust, if possible

In an ideal world, you should be able to choose your doctor and establish a long-term relationship with them. You may prefer someone who has a similar background as you, or speaks the same language if English isn’t your first language. But if that option isn’t really possible, there are other steps you can take.

Bring any of your own research or past medical documents

Do you have a long-standing condition that still hasn’t been resolved? Keep a journal whenever you can of specific symptoms when they happen, including how long certain symptoms last.

If you’ve worked with any other medical practitioners in the past to understand these symptoms, bring along any paperwork or notes you have on that, too. Giving as much context as possible helps set a foundation for the history of your symptoms — and may help you argue your case better than just with words that disappear into the air.

Come prepared with a list of questions or points you don’t want to forget

Doctors often rush medical visits due to their packed schedules. When that happens, it’s so easy to get flustered and forget to bring up important points or questions. Write down any questions you have and bring them on your cell phone or a piece of paper. Having that in front of you will make it easier to advocate for yourself in the moment.

Write down and express your boundaries early on

You should never feel unsafe or like your boundaries are being violated at a medical appointment. Think about what makes you feel most comfortable and safe before the visit. Write these down and think of straightforward ways to communicate your needs if your medical provider tries to cross any boundaries.

For example, that might include boundaries like:

- “I’d like to discuss my symptoms before I change into a robe.”

- “I would like you to tell me what you’re doing during the examination while you’re doing it.”

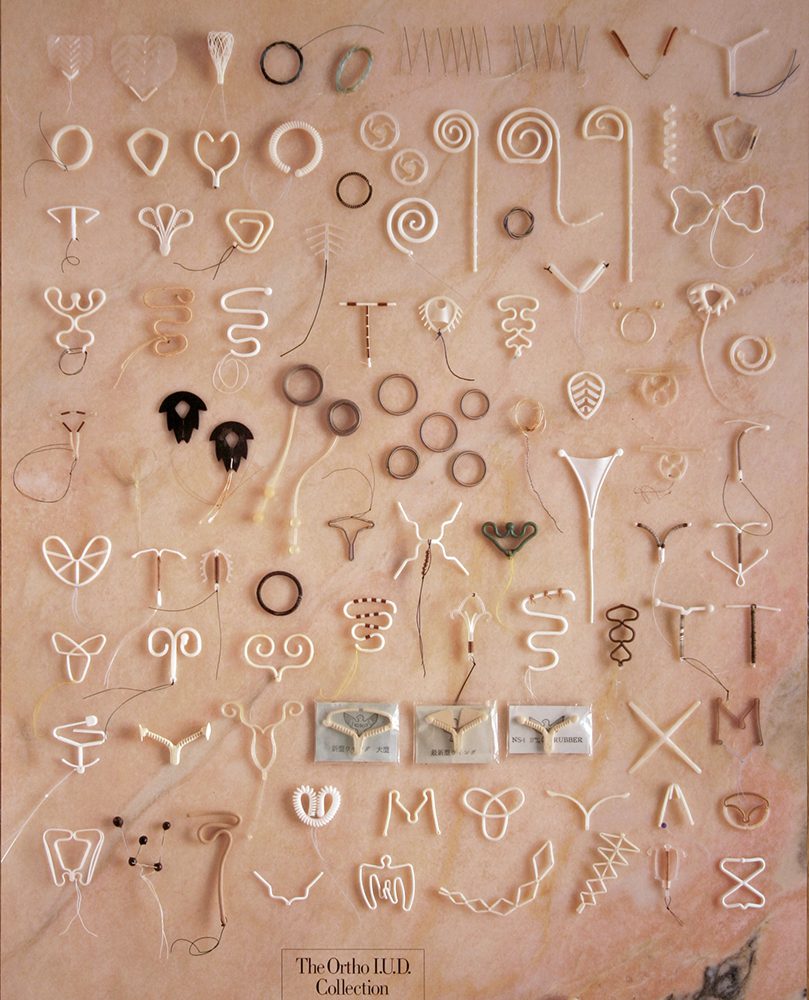

- “Please warn me ahead of time when you’re about to put in the IUD.”

Speak up if you’re feeling dismissed

That little voice inside of you knows when something is wrong. If your doctor isn’t taking stock of what you’re saying, don’t be afraid to say it over again. Repeat how severe your symptoms are, or make it clear that you’re not comfortable with next steps.

For example, you may say something like:

- “I don’t feel safe leaving this office until we have a plan in place to address my hemorrhaging.”

- “I have had extreme period cramps for seven years now, and I know this is not healthy or normal for me. I want you to test me for signs of .”

- “My depression has been really bad lately and I think it has to do with my birth control pills. What alternatives can you offer me?”

Bring a partner advocate with you if you’re comfortable

Sometimes it helps to have someone else in the room who can help back up the symptoms you’ve been experiencing, or act as an advocate when you’re feeling emotionally or physically overwhelmed with pain.

If you think you’re being gaslit due to your race, gender, or sexual orientation, this can be a great opportunity for an in your life to step up and use their privilege to advocate in partnership with you. Of course, if you decide to do this, it’s important to discuss with the partner ahead of the appointment how they can best help you.

Document your appointment, including the help you did (or did not) receive

Even if you’re a great advocate for yourself, sometimes a doctor still won’t be willing to take your symptoms seriously. Behavior like that is both unprofessional and unacceptable. When happens, it’s important to write down what happened in the appointment, and seek out a different opinion if you’re able to.

Get the Free Checklist

We know how overwhelming it can be to advocate for yourself during a medical visit. That’s why we made a free checklist — so you can come to your next appointment prepared.

This is an interactive PDF that you can fill out and print out, or bring on your cell phone. Either way, it will give you some relief and peace of mind to know that you’re entering a medical visit prepared with the best tools possible.

If you’re looking for the right for your body, adyn can help.

-

- Villarosa, L. (2018, April 11). Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html

- Hafeez, Hudaisa. “Health Care Disparities Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: A Literature Review.” NCBI, Cureus, 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5478215.

- Chen, Esther H. “Gender Disparity in Analgesic Treatment of Emergency Department Patients with Acute Abdominal Pain.” Wiley Online Library, Academic Emergency Medicine, 2008, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00100.x.

- Petersen, Emily E. “Vital Signs: Pregnancy-Related Deaths, United States.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2019, www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6818e1.htm?s_cid=mm6818e1_w.

- “Racial and Ethnic Disparities Continue in Pregnancy-Related Deaths.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019, www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0905-racial-ethnic-disparities-pregnancy-deaths.html.

- Brennan, Sabina. “Medical Gaslighting: The Women Not Listened to or Viewed as Overdramatising or Catastrophising.” The Irish Times, 2020, www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/health-family/medical-gaslighting-the-women-not-listened-to-or-viewed-as-overdramatising-or-catastrophising-1.4386203.